John Bryson

Author, Journalist and Lecturer

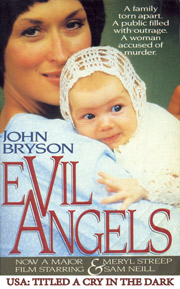

Evil Angels

Also a movie with Meryl Streep and Sam Neill, directed by Fred Schepisi known as A Cry in the Dark in the USA and Europe.

A documentary novel, literary journalism, long-form reportage.

The infamous ‘Dingo-Baby’ case began at a crowded tourist camping ground alongside the huge Ayer’s Rock, in the Central Australian desert, at dusk, while most families were cooking at barbeques, as wild dingoes prowled the shadows sniffing food.

The Chamberlain family has arrived the evening before. August is a gentle month in the Centre. Visitors expect a warm easterly breeze of an afternoon, dropping out at dusk to calm evenings. As it was when the yellow GM hatchback turned in here, carrying the Chamberlain family, Lindy nursing her sleeping babe Azaria, now just nine weeks old, Pastor Michael driving, and the two young boys Aiden and Reagan in back. This second evening, the babe and Reagan asleep in the tent, the adults shared barbeque space with a Tasmanian couple, Greg and Sally Lowe.

SALLY LOWE HEARD the baby cry. Not loud, but sharp in the cold air, and somehow unfinished. It was this property of curtailment which moved her to look at Lindy. Lindy was not bothered and, given that a mother’s ear for the sounds of her own is naturally more accurate, it seemed best to Sally Lowe that she hitch her Chantelle higher on the hip and say nothing. Considerations of parental infallibility were lost on Aidan. ‘That was Bubby crying,’ he said fearlessly. Michael then agreed he’d heard it too, and Lindy turned for the path, through the low bush to the tent, with skeptical strides. ‘But she was fast asleep,’ she said.

FROM THEN ON, it would seem to everyone that things happened in different dimensions of time for each of them. Lindy Chamberlain’s quick legs, as she makes over the scrub, take on the jerky impulses of panic. She falters, but this is associated somehow with taking the last eight or ten paces to the tent at a run. Sally now realizes that Lindy has shouted something to them all, something terrifying and engulfing, but cannot yet arrange the meaning of it in her mind. An earlier thought is not yet displaced: the sports parka Lindy has on looks comical over a floral frock and bare knees. Lindy, who curiously seems to be the only one with the capacity for movement, drops to all fours and scrambles inside the tent. It is her reappearance then, with unrewarded arms, that locates for them what it was she had said.

Sally, sturdily akimbo, thinks she has heard the word ‘Michael’ before anything else, and makes an effort to look at him. Greg, leaning on the bench, misses the first words but is slowly getting the rest. Michael, holding over the flame his wife’s tardy meal, seems to understand least of all. And Judy West, now bolt upright in the chair inside her tent, has heard the cry, ‘My God. My God. The dingo’s got my baby.’

Greg was the first to escape whatever force it was that held them down. By the time he reached Lindy she was already at the rear of the tent, facing the road. Michael was now abreast them, but not yet abreast the train of events.

‘What?’ he said. Lindy’s response was no answer but an attempt to part the currents of turmoil: ‘Will somebody please stop that dog?’

But Greg could see only an empty road and night beyond. ‘Where?’ he asked. ‘That way,’ she pointed, across the road and to the right. That way was pitch black, a fact which struck them with the force of a new and unpredictable circumstance. They needed light. Lindy threw back her head. ‘Has anybody got a torch?’ she shouted. Sally Lowe made for her car. Aidan scrambled to find the torch he had a minute ago. Judy West, who had found no one at the barbecue, reached them all in time to grasp what was going on and headed back for Bill and Catherine and for a lamp. Greg snatched a flashlight from Sally’s advancing hand, as though he were about to run the final leg of a relay race, and sprinted for the brush.

There was an inexplicable moment between the assent of the switch and the sudden expression of light. The tops of bushes shone back, unruffled. The shadows were dark and abrupt. The brush seemed more tangled than it was in daytime, the sand softer. Spinifex and wattle slapped his thighs. Somewhere to his right, he could hear someone else stumbling through the growth. Greg held the beam higher. It was Michael, threshing the scrub aside with both arms and squinting at the ground. Evidently he hoped the dingo might have discarded his baby in flight. He had no torch. The blind flailing of those arms moved Greg to a declaration of sympathy and of common anguish, but the thought was inexpressible. ‘What a hell of a thing to happen,’ was the best he could do. The first thought of Chief Ranger Derek Roff, summoned to organize a search was, ‘So, it’s finally happened.’ He had been warning his Government Minister that it would. Searching continued well into the night, hundreds of searchers, campers, black-trackers, police rangers. It continued next day. The Chamberlain family was taken in by a local motel. City police investigators arrived, as did the first journalists.

In the barroom of the Red Sands Motel, the night after the search began, the first journalists here drink with police who have flown in from Alice Springs. A detective and a journalist are vehement in their denial of the Chamberlains’ version. No history of a death this way ever before, becomes their frequent jibe. The detective storms away, returns with a plastic bucket of sand. This is the weight of Azaria Chamberlain. He insists each try to hold it for one minute in the teeth. Perhaps because of the laughter, none is able. A silly incident, but the first of many trials and experiments to come in laboratories and in the field, with which it has in common three notable aspects: it is kept secret, it is not subjected to testing, and it begins a fresh set of rumours against the Chamberlains. Precisely here, and at this moment, humankind took over from dingoes in the harassment of this depleted family; at this moment began the contagious scepticism which would infect a core of investigators with a belief in the Chamberlains’ guilt so deeply that they would deny the usual practice of fair disclosure, gather evidence later exposed as fallacy, open proceedings against the Chamberlains in a secret court, manage the reporting of a looming prosecution by news releases to friendly journalists, forbid their scientists to release their findings for peer reviews, destroy evidence of blood testing so it could not be examined at the trial, cause this religious family to suspect they are the tragic playthings of their God, and press to a successful conclusion The Azaria Murder Case, this vast stupendous fraud.

Mrs Chamberlain spent two and a half years in prison for murder, husband Michael bonded as an Accessory. The Trial Judge left the bench to campaign against the use of juries in criminal cases. All the campsite eye-witnesses banded together in travelling road shows, lecturing public gatherings and calling for the release of Lindy Chamberlain.

This book, Evil Angels, was first published by Penguin Books and released in 1985. Lindy Chamberlain was released in 1986. A year later a Commission of Inquiry concluded the scientific evidence called by the prosecution was flawed, all of it unscientific, much of it fraudulent, and cleared the Chamberlains, who were then paid compensation.

Evil Angels was translated widely around the world, and published in 1992 by The Notable Trials Library, with this introduction:

It is an extraordinary chronicle not only of Australia’s most controversial trial, but of an entire nation’s obsession with a whodunit that is unique in the annals of legal history. Alan M Dershowitz, Professor, Harvard Law School.

In an ABC Radio interview, Michael Chamberlain said, ‘I can never thank John Bryson enough.’

Evil Angels won three Australian and two international awards, including the British Crimewriters’ Golden Dagger.

Please see The Azaria Papers page.

The Conversation E-Magazine, March 5th 2014 asked, “If you had to argue for the merits of one Australian book, one piece of writing, what would it be?” Here is “The Case for John Bryson’s Evil Angels” by Professor Kieran Dolin, English and Cultural Studies, University of Western Australia.