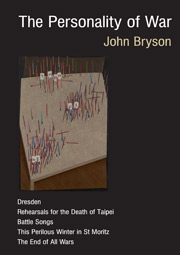

John Bryson

Author, Journalist and Lecturer

The Personality of War

Comprising four pieces.

Rehearsals for the Death of Taipei.

One day every year Taiwan practiced its defenses against its possible invasion by China, or for its own invasion of China. Here is the moment in Taipei.

Air-raid sirens reached high into their registers to reach over the messy noises of the city, and there didn’t seem to have been any precise point at which, pure and harmonic, they began, merely a time when everyone noticed them together, and the sidewalk population of Taipei stood, for the moment, still.

Everyone knew this was a rehearsal, the one alert of the year, a practice-run for another day altogether. The days on which it might fall were listed in each of the sixteen city newspapers and broadcast from all the radio stations. Everyone knew there were no specks at high altitudes, no mean lines of vapour, nothing was up there right now, but it was impossible not to look at the sky.

The End of All Wars.

Four stories, moments which ended World War Two, moments for a small band of German women who formed a chamber orchestra in a cellar in East Berlin, moments for a fighter pilot in New Guinea who disobeyed the cease-fire, for another pilot who was exercising in clouds over the Arafura Sea when told the war is over, and the end of the War in Vietnam for a soldier so damaged by warfare he brings cruelty home with him as if it were a trophy.

The bells of our two cathedrals, the Catholic and the Anglican, rang out over the street while policemen on point duty slowed the traffic below, they pealed between the office blocks and the department stores, to the stone towers of the small kerbside chapels where, like a feast day procession, they brought out of doors the chimes of Saint James and the chimes of Saint Francis and then the deep Wesleyan on the hill and , as everyone watched from the footpaths, together they rang all the doves of the city into the air.

Dresden.

Now an old man, a onetime Air Force flyer recalls his time in the night sky during the bombing of Dresden.

For the incineration of a hundred and forty thousand souls, if things went right, for the destruction of a graceful city, of its old walls and obedient gardens, they flew east. He was the navigator. They were flying in at fifteen thousand feet, in the left lane of the crowded sky, which made the heading and beam angles easy, in the last wave of bombers but one.

This Perilous Winter in St Moritz.

Holidaying at St Moritz as he had since childhood, German industrialist Herr Genscher rides the cable car to the mountain top to meet his son, and recalls his vacation here on leave from World War Two, as did resting British officers, sharing the ski runs.

‘During the war I was here,’ Herr Genscher says. ‘So also were officers of the French and of the English. Not many, you understand, but some. We all behaved so very well. We stayed at the same hotels. We said Good Morning in the foyers and at breakfast. No one was in uniform for we were all technicality tourists. That was 1940. In 1940 there was a new battle somewhere every day.’